Climbing my first 5.14a with Lattice Training – Part 2

This is a story of a journey to climb my (Adam Fiala) first 8b+ (5.14a). Climbing 5.14 can be perceived as an elite climbing performance, but the fact is that this grade is being climbed way more often nowadays. This, however, is not the point. I chose to write a story for a different reason. I couldn’t get to this grade “just” by climbing and I had to learn a lot of new things and step out of my comfort zone. This might as well be the story of how I climbed my first 5.12 or 5.13 but it so happened that the process to climb 5.14 was the most challenging but also the most memorable one.

Following A Training Plan with Lattice

Winter of 2020/2021 was really special for me. It was the first time I had trained consistently for multiple months in a row – uninterrupted by injuries, life obligations or anything else.

After my initial summer stint of training I knew what to expect moving forward. My coach Raf got to know me a little better, and the hard part of finding the right training load was already done.

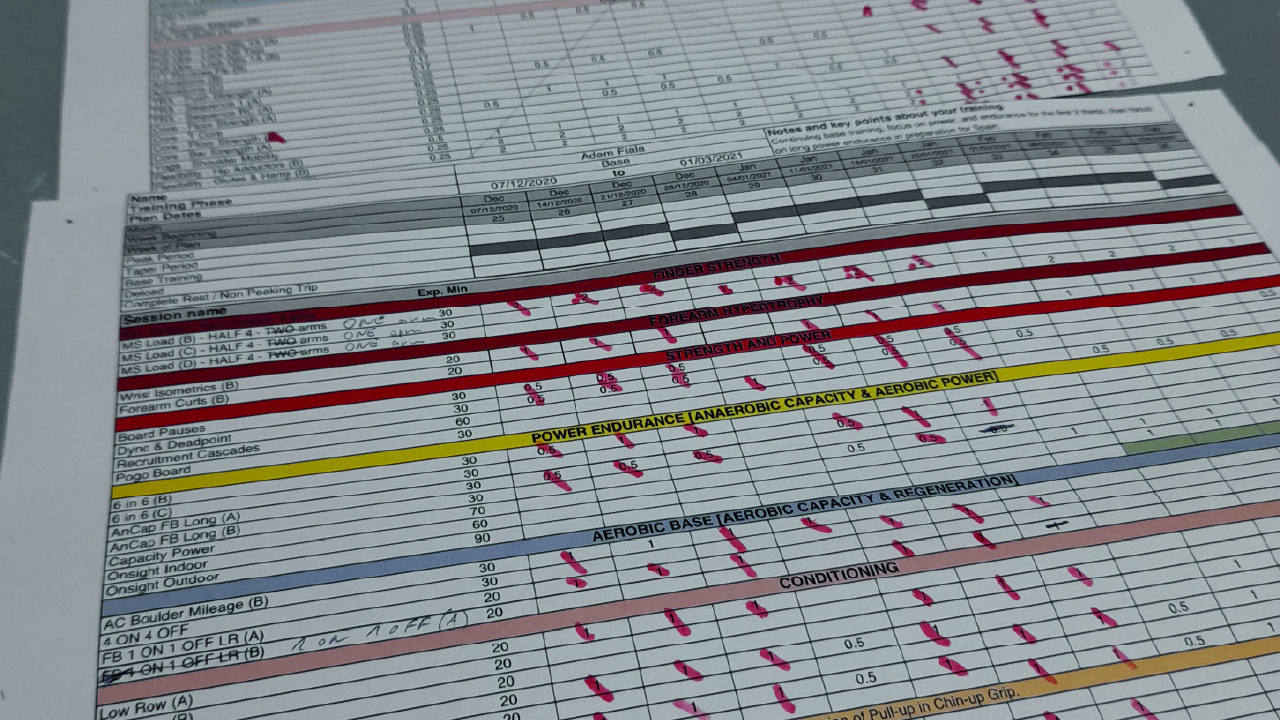

Below is an example of my training week. But first, a caveat: : This program probably won’t work for anyone else. The focus and volume of any training program should always be determined with regard to the specific needs of the individual. This is not one of those articles that tell you “How to train for 5.14 (or 5.13 or 5.12)”.

For me personally, I believe that using those types of training resources in the past was not only useless, but even counterproductive in a sense. Why? Imagine that you are going to build a house. You know that you need a foundation, so you study everything about foundations and decide to start by digging a deep hole. You pour the concrete in, and after some time your foundation is finished. It has rebars, top concrete mixture and precise formwork. Except that you have no idea what the house will look like. Did you even build the foundation where you needed it? Is it strong enough to support your house? Or maybe it’s too strong and you wasted your money? In the end, you might realize that using such quality concrete and spending time with formwork was completely unnecessary for your foundations. You wasted your resources and energy while missing the bigger picture. What you need is an architect. This person will not only make plans for your house but will also ask you questions about what you expect from your house. And last but not least, they will convince you that some of your ideas are probably wrong.

What did my Lattice plan look like?

I told my friend I trained with Lattice the whole winter and he asked me: “What new things did they make you do? Did you get any new exercises?” I started naming workouts that I had in my program: hangboarding, arcing, bouldering, 4×4’s, stretching, rings, pull-ups, push ups, core and so on. The disappointment in the eyes of my friend made it clear that he expected something else. Probably a secret sauce that Lattice feeds to their athletes.

The ups and downs of training sessions

One of my climbing sessions was focused on anaerobic capacity. For this session I was supposed to do “6 in 6” which meant six boulders in six minutes (climb a boulder, rest for the remainder of a minute and repeat 6-7 times for 3 sets). I mention this particular session because it was the one that I had the most intense love-hate relationship with. It was tiring both physically and mentally. You’re out of breath, trying to recover for the next boulder and by the end you’re powering out. There is never really a sense of control or ease because you gradually make the boulders harder as you get better. I think the most challenging and rewarding part was the feeling of exhaustion after this workout.

The other workout that felt utterly exhausting was pull-ups. It sounds trivial and it is – just pull-ups, nothing else. You might wonder why I needed a Lattice program to do pull-ups. Well, it’s simple. If you hate doing something, you never make yourself do it. You don’t even acknowledge that you should do it. Oh, how I hated pull-ups. Every time I did them, it seemed that all parts of my body lit up with uncomfortable sensations – either my lower back ached, my neck got stiff or I got a bit dizzy. However, it seemed that there was one simple recipe to improve at pull-ups: just do them regularly, twice a week, every week, without exception.

Bouldering and hangboarding were things that I enjoyed the most. Low volume and high intensity sessions were my thing. However, there was a new challenge in these familiar workouts. Due to the fatigue from all the training, I had to drop the intensity (usually by 5%-10%). According to my coach: Not a big deal for training stimulus. However there was another aspect of my training that suffered from this, and that was bouldering with my friends. To keep up with my already strong climbing partners, I would usually show up rested and recovered as much as possible – a luxury that wasn’t possible anymore. I was flailing on the boulders, hardly stringing two moves together. In an ideal world, I would stand unaffected; embodiment of a zen monk quietly repeating the mantra “training is not performing” and I would just climb easier boulders.This temporary drop in performance became more obvious when climbing with others and made me doubt if all this energy and money that I was putting into training was worth it. To ease my doubts and silence my ego, I resorted to training alone. That allowed me to adjust the difficulty of the boulders accordingly and my sessions were more effective.

How much did I actually train?

My coach made a few iterations of the program based on my feedback. In practice it meant that we would take away a workout or two until I was able to complete a given training period without getting burnt out. And even after that, my coach tweaked my program often as each block was different and sometimes proved to be too much. I can imagine that it could go the other way around for some people, who would perhaps end up adding workouts, but that was not my case.

What was most “concerning” for me was the amount of climbing sessions. With each “on-the-wall” session being under an hour, I didn’t spend more than 3 hours per week on the wall. With the Lattice Plan my climbing sessions were targeted at different energy systems and as a result they were more taxing – for example anaerobic capacity was my nemesis and by far the hardest climbing session for me. Secondly, the sessions effectively eliminated the “junk mileage”. So even though I might have done less in terms of number of sessions, the quality was much higher. As a side note, I did share my doubts and concerns with Raf, and he did a great job of explaining the reasoning behind the plan. This reassured me, and helped me to successfully finish the winter of training.

When I asked what the average 8b-8c climber could handle, the amount of training Raf suggested for an average 8b-8c climber was almost 1,5 – 2x bigger than what I was able to do. And that’s exactly it! Everybody is different and has a different training history. It was interesting to read it and compare myself to others but at the end of the day, I had to stick with what my body could handle anyway.

The beauty of a personalized training program is that everyone can start somewhere and build up to do more over time.

- I probably trained less than “average” 8b climber but the program was adequate to my training history (I had smaller tolerance to physical training, was slower to regenerate etc.).

- My training program was a little “heavier” on conditioning because it was my weakness. Hence I had a little less “on the wall” time. This split makes complete sense because I always just climbed and never really did any general conditioning (pull strength, push strength, core). I am also not naturally strong in this area.

- Everyone can manage training differently. Training history should be the main determinant of total workload. I can easily imagine 5.13 or 5.12 climbers that are able to get more training done than me.

Returning to my project: sending time

In March 2021, I finished a four month training block. My friend asked me: “Aren’t you afraid that all this training won’t work?”. I believe that the usual perception of someone making sacrifices is that in the end it will be “worth it”. However, if you’re trying something for the first time in your life, you don’t know if it works. Justifying all your hard work by getting a reward is a risk that might cause a lot of anxiety in the process. Somehow, I got into the mindset of not setting high hopes on successfully climbing the main project. I put myself through all this effort and hard work, knowing that I might not achieve my end goal. It was something I’ve never experienced before and it fascinated me – I found that there was something magical and deeply satisfying about it.

In June I finally got back on my project. When I tied in I am not sure what I was thinking but I definitely didn’t expect what came.The moves still felt quite hard but I just kept going. I passed my high point from last year and continued through the cruxy cross-over move. I also made reachy undercling move to the right and found myself well past the point that I could imagine stringing in one go. After that I fell and I immediately realized that it was a surprise, rather than a pump or error that pulled me off the wall. On my next go, after two minutes of wrestling the overhang and breathing hard, I found myself just below the anchor, once again surprised by myself to the point where I hesitated and fell. This time however, I realized that I can send the route. The big question mark looming above many months of effort was gone and I knew that the training worked! I tied in again and set off, once again feeling in control all the way to the last hard bit below the anchor. I reached to the right hand gaston, sorted my feet and grabbed the undercling with my left. Now only one thing remained, a blind backstep to the opposing wall, allowing me to suddenly transition from hard climbing in the overhang to a no hand’s rest. I grabbed the undercling and for the first time I felt uncertain, panicking at first when I couldn’t feel the wall behind me but finally finding it after a split second. I shakily clipped the anchor, hardly realizing that it’s over.

Is a Lattice plan worth it?

Following the Lattice training program came with more benefits than I originally thought.

The biggest one for me is that my physical resilience improved. My joints felt healthier, the chronic pain from golfer elbow has disappeared since. I believe that is mainly due to the upper body conditioning and putting on more muscle mass. Consistent hangboarding did a great job for my fingers which are not as tweaky as they used to be. My lower back that was frequently painful is doing alot better now. Not to mention that I feel physically better in activities unrelated to climbing (like ski touring!).

Another noteworthy advantage of having the training program written by someone was that it took some anxiety away. When I “self coached” I was quite often questioning my decisions and that made it really hard to follow a program over a long period of time. As a result, I never really stuck to a training program for more than one or two months. Perhaps it’s a personal thing but handing keys to someone else made it easier to trust the process. Therefore, when doubts did creep in I simply communicated them to Raf and he explained why we do, what we do.

Of course, having a coach is not only important because of the expertise. I received a a lot of support from Raf which I am especially grateful for! Not to mention, the conversations and interactions with another psyched climber never gets boring! Thanks Raf!

The hard truth about training

When I hear something that sounds “too good to be true”, I immediately get defensive. I don’t believe that “magic bullets” exist, at least not in the world of climbing. I even feel weird about the way I wrote these last few paragraphs that, despite being written in all honesty, sound like a highly suspicious sales pitch.

Yes the benefits I got from the training were great, however there was hardly anything magical about the way to get there. Almost eight months of consistent training was a lot of work, it included missing out on other activities and a lot of compromise.

That brings me to the title of this paragraph. The truth is that you have to do all the work and the training plan is nothing without solid adherence and dedication. When I first got the color coded table with the layout of workouts for upcoming months I was very excited, like a kid with a new toy. That feeling didn’t disappear. But after a few weeks of training, I realized how much work each and every workout in that table represents.

Another realization I made was that the training is quite boring. One interesting aspect related to climbing is that we seek novelty in the outdoors, an environment that brought us to climbing in the first place. And yet, our need to experience adventures might be in direct competition with our desire to improve at climbing. The balance between spending time outdoors and my dedication to training is a puzzle I did not yet solve. I doubt that anyone has a good solution to this. I guess we have to do our best to find what works for us knowing that this is not the worst problem to have.

Final thoughts

If anyone got this far – thank you. This blog is for anyone but I hope that there is at least one person that could relate to this story through the love for climbing and the desire to improve.

I am fascinated by how much climbing did for me. Not only is it a great physical outlet, it is also a practice that helps me find balance in life.

For people who have this ambition to improve – I wholeheartedly recommend to act on it. Most of us are far from being sponsored athletes, making the hardest ascents in the world or winning a competition. Our goals might feel insignificant compared to the world’s best but what isn’t? Unlike the popular belief, I think that we don’t search for the purpose of life, we create it. Or, like my friend once told me while holding a beer and putting up plywood in his non-profit bouldering gym: “You gotta do something in life”.

The hardest part for me was to realize that in fact I don’t have to justify any of it. I learned to allocate my time and money to climbing without feeling any guilt or the need to explain myself. Knowing that this little world of training and climbing is not something I need to constantly present to the rest of the world gives me enormous satisfaction and also freedom to pursue any goal I set my gaze on.

To read the full 5 part version of Adam’s Journey to Dance with the Wolves go to his website.

Want to start your training journey? Sign up to our Performance Coaching Plan!