9c, Adam Ondra and Alex Megos

The big grade of 9c has officially landed! Adam Ondra has succeeded on his Flatanger Project Hard, undoubtedly the pinnacle of his climbing career to date. The 9c grade is obviously a big number – almost too big for some of us to comprehend – but how big is it? What does this benchmark on the grading scale really mean?

We thought it might be interesting to look at whether Adam’s performance could potentially be matched by Alex Megos. To do this we’ve taken a few basic elements of physical performance and made some broad assumptions (yes this is a “fun” article and not super serious!) about what’s required to achieve 9c and whether… yes, the big one…. could Alex Megos actually go out and do 9c fairly quickly if he really wanted?

Lattice Training assessed Alex last year in 9b form and it was very interesting to look at his physical profile. The work that he has done with Dicki and Patrick over the years is superb and Alex’s attitude towards hard work stands out a mile. He’s got the special element of “try hard” that few athletes ever achieve and a physical profile to support it.

Ok, let’s look at the numbers!

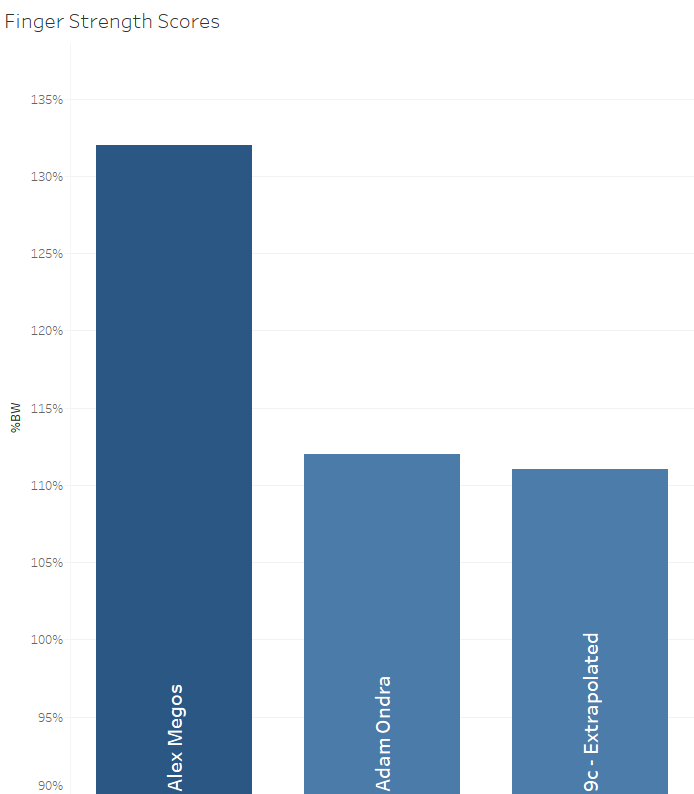

Finger Strength

Absolutely the number one starting point for any profile. How hard can the forearm muscle contract and how does that relate to body weight. We saw Alex achieving an almost superhuman 132% of body weight carried on our test edge and our best information on Adam is that he’s pulling 112% of body weight (although this was from a previous study a number of years back – Balas et al). I was talking to Adam in Spain this year (between redpoint attempts on a 9b!) and he still considers himself to have weak fingers compared to many elite climbers – I guess we have to trust that he’s objective!

In terms of the data that we analyse, we would expect a 9c redpointer to be hanging a minimum of 111% of bodyweight on our standardized test edge. So theoretically both Adam and Alex hit the benchmark, but the latter is way above what we would expect. No surprise he does well in the Frankenjura!

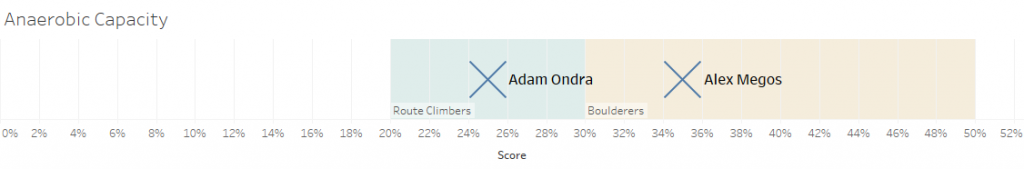

Anaerobic Capacity

The ability to produce high levels of lactate at a fast rate is critical for any athlete who demands performance in short windows (think crux sequences or long boulder problems). Typically we see those who favour short powerful routes scoring >30% on our scoring and those who perform well on long sport routes as having 20-25% score in anaerobic capacity.

As we saw in our testing, Alex had a predictably high AnCap of 35%. This is completely expected considering his love of bouldering and short limestone routes. If we were to test Adam, I’m fairly certain we would see AnCap scores closer to 25% which would mean you’d perform extremely well on long sport routes and as long as finger strength was adequate, it wouldn’t be a limiting factor on shorter routes either.

Aerobic Efficiency

So here’s the real key. How does the aerobic efficiency of a muscle compliment with the anaerobic side? For those athletes who wish to get the most out of the finger strength they do have and also perform well on routes that take 4+ minutes, then it really is essential that the metabolism of aerobic energy is extremely high. If it’s not there, then it doesn’t matter how strong your fingers are (within reason!) you just won’t get up that 40m stamina-fest.

We know that Alex scored reasonably well on aerobic efficiency but was a significant margin away from the very highest scores. Having watched Adam’s performance over the years on multiple, long, hard onsights, recovery on rests and knowing Patxi’s approach then I think we can be very confident in saying his localized aerobic training has been entirely appropriate!

The Future

If I were to hazard a guess – and of course this is just based on experience and access to a nice big database of numbers – then I predict the following:

- Alex can climb 9c (or more) if he is to improve aerobic efficiency, gain movement economy or improve route tactics like unusual rest positions, speed or greater flexibility for specialist moves.

- Adam will struggle to climb harder than 9c without addressing basic levels of strength and power as he’s already such an efficient climber. Just a single step up in strength levels would give him access to the next grade. Perhaps project hard is just the first step in this direction?

Finally…. Please remember this is a lighthearted look at Alex and Adam’s performance. We’re having some fun and hopefully providing you a look at what it requires to climb at these levels.

Hello, I think Adam’s finger strength figure 112% is not accurate in this article. As you mentioned, this figure came from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19346182.2015.1012082, where Adam was referred to as “the only high elite climber”. However, in this article the researchers measured the climbers’ finger strength in 4 different grip positions: a)open grip, b)crimp, c)middle and ring finger, d)index and middle finger. Adam achieved 117% in open grip test but 112% in crimp test. So I think it’s better to take 117% as Adam’s finger strength number.

Considering that no matter which grade you will never have to pull significantly more then 100% of your weight (body weight plus gear) would it not be more interessting to find out on how small a hold and for how long an elite athlete can hold 100% to try to figure out what the theoretical max grade could be?

If you do a pull up you are exerting more than your body weight on the bar, that’s why your body moves up. Similarly, if you do a really powerful move off a small hold your fingers are exerting more than bodyweight on that hold.

You didn’t get that 112% body weight means you pull your body twice plus 12% more, did you? So Adam Ondra can pull himself plus 84 kg more.

It’s not about you will never have to pull such weight. It shows strong you are anyway. If you’re stronger, you’ll more like pull up yourself on a small hold and you’ll more likely keep more energy when pulling on a more convenient hold, you’ll keep climbing longer. How long can they hold a small hold is more about the finger strength. These two tests combined say pretty much. You can use/develop different test but it will just give same results expressed differently.

That is crazy to think about. I’m 180 pounds and 5’8 and hanging off the BeastMaker 1000 edges on the bottom (18-20cm mor it less) with 105 pounds for 13 seconds at the beginning testing of my programming after a 4 month wrist injury. Actually tomorrow I’m testing the same edge doing 1 arm hangs for 13 second max with assisted weight tomorrow and doing a version of the 7-53 hangboarding (love it and it saves time with more time under tension without any loss of strength at the 7 second mark). This puts me at maybe being able to hang for 13 seconds off the beastmaker 18-20 mm edge at 142 pounds, or 37.5 pounds assisted. I figure a half a year would bring me down to being able to hang with 160 pounds with 1 arm.

I’ve always had a suspicion that my body weight, and not my finger strength, has been my limiting facor at this point. My BMI is 27.4. If I was a 140 pound climber, I could (theoretically) hang from a 20mm edge for 13 seconds at body weight with 1 arm.

I love seeing what the pros can do, it gives me inspiritation to at least think I can climb harder (loose beer weight).

I don’t understand why you refer to 13 seconds. I don’t understand your calculations. It makes no sense to me. Hanging without any weights is hanging with 0% body weight.

Hi Tom,

Can you please explain the procedure that you have used for the assessment of anaerobic and aerobic capacity? I don´t understand how you obtain the scoring percentages that you refers.

Thank you very much

Pedro

Even though the article is not meant to be to serious, I would expect a smaller, lighter climber to have better test values than a taller one. As we know, that does not always mean it is better to be short, as you are forced to do “longer” moves and probably need more physical strength.

Hi Ollie,

that’s right! Of course you can retrain muscle fibers in terms of recruitment, but an earlier innervation of FT-Fibres can cause earlier fatigue, too.

Maybe a more neglected effect than the measurable and objective finger-strength is the intermuscular coordination of the different finger flexors. Considering the specific grip techniques can lead to an enormous increase in effectifeness, away from age related windows or years of training. It should be present every time in training! On the other hand I think, that the optimum exploitation of specific “windows” in climbing performance training hasn’t reached a satisfying state yet.

Yes I do strongly believe that the personal pace is something which should be highly adaptable. But you will need some “trajectories” at all.

I think that we will see more specialisation between outdoor and indoor climbing in future. The indoor guys will compete in their early and midtime careers and then will change to rock. Nevertheless in future we will also have have some top climbers who only concentrate on outdoor performance and I like this!

Looking forward to seeing you in Sheffield!

Best

Patrick

Hi Patrick,

can you please explain “Considering the specific grip techniques can lead to an enormous increase in effectifeness, away from age related windows or years of training. It should be present every time in training!” a Little bit more?

How can this actually be trained?

Simon

Hey MICHAEL HEINSTEIN,

This is of course a very good point which we totally agree with. However, I will still refer to use of dynamic sport specific strength being generally a proportion of maximal controlled strength.

This can be seen in slower or even static movements (strength) being much higher than the those produced during the event (power). Therefore, despite climbing being dynamic the ability catch and move round a hold must surely be a percentage of the strength applied to a controlled static hang.

The question then comes in as to what percentage of this force is being accessed. For instance, a climber who fingerboards a lot may have exceptional finger strength but cannot apply the force quick enough to catch a hold during a dyno. Whether the two climbers mentioned in the article differ here I do not know. But we are working on methods to test this in the future which obviously has many safety issues. But fingers crossed the data looks good so far 🙂

On the subject of back and shoulder girdle stability I couldn’t agree more. Once again I believe this limits the range of use of finger strength function but perhaps not the basic strength during a dead hang test for athletes at this level.

KNUT ELDE JOHANSEN OG as Remus has said, this is fun article designed to promote intellectual discussion. In this case, the article has been a success on many platforms sparking academic debate among a large group of psyched peers. We pride ourselves at Lattice on working within the principles of sport science research and have stated this is not part of our usual data output. We also do not want to offend any athletes we do not work (or the ones we do either). I hope you can understand this and enjoy the theoretical discussion of the subject rather than the validity of our article.

Ollie Torr

I think the only reason, as he also said in an interview, is that he never dedicated himself to a project for a long time. If he ever decides to, and I’m happy he doesn’t yet, he can do it.

Hi,

Very interesting approach to assessment of climbers, BUT please, you only really have numbers from one of them, and you keep on guessing throughout the article, which totally undermined everything you try to talk about. This is neither comparative or scientific. I guess the article attracts so many people with those names compared, but you don’t compare you guestimate. I think your approach to trening looks very interesting, but this article should never been written, like it is.

Hi Knut

Thanks for the feedback. We tried to make it clear early on that this isn’t a super accurate comparison, rather it’s more some light hearted speculation. Sorry if that wasn’t clear.

Remus

Ollie,

Really interesting analysis. One question – finger strength in many of the modern studies of climbing is done statically, while climbing is a dynamic sport. I wonder if this method has a significant degree of inaccuracy? One interpretation from your analysis – given Alex apparently having stronger fingers, his bouldering might be expected to be 1-2 number grades harder than Adam. We also know Alex has a much stronger back if you measure it via one arm pull up ability, for example. But Adam has in fact bouldered harder than Alex. My guess is climbing specific strength is more specific than hang strength, and the utility of back strength in far nuanced than one arm pull ups. The ability to maintain strength in the face of dynamic moves, eccentric contractions, etc….all of those come into play during climbing, but not hanging. The ability to use your back muscles in unique angles, lock-offs, etc…is perhaps more relevant that maximal strength in many of the back tests. Modern training has made climbers do really, really well at these standard tests of strength…but this strength is not super accurate at distinguishing between elite levels climbers. It can likely distinguish between a 5.13 and a 5.15 climbers for sure…but perhaps not that much more accurately.

Hey Patrick,

Good to hear from you! Thanks for the comments, it’s great to get a closer insight into the athletes and performances we have provided fun theories too.

It is interesting to read your thoughts on finger strength being limited by the improvement during the window of opportunity (age) once at an elite standard. Though I agree with the concept that this is the prime time to make improvements which underlie the rest of a climbers career, it seems slightly simplistic to suggest a limit is set during this period of development and that it cannot be manipulated through reductions in muscle efficiency. Perhaps the muscle fibre strength has reached a set limit based on the genetics and training at the correct age but would retraining the recruitment of muscle fibres not allow a better expression of strength? Unfortunately the catch 22 is with retraining this the efficiency that allows sustained efforts would drop anyway. But it would be interesting to hear your thoughts on the possibility of retraining.

Totally agree with your comments on aerobic function. We often see people overlooking this aspect believing a limit has been reached due to strength alone. Obviously we know MVC does play a role in how aerobic one can stay on a route but fundamentally if, as you say rhythm and rests are optimised, most climbers can perform better through higher aerobic function.

It’s really interesting to hear that you have worked with Alex on his personal climbing rhythm. We often see pace being individualised for athletes in different fields (trad, boulder etc) but its great to see you have put this into practice through experimentation. Do you believe this pace could be allowed to change based on the type of holds found on granite compared to limestone?

I assume the extensive interval sessions you are referring to are longer easier bouts of climbing. It does make sense that ingraining different movement patterns through higher volume at an unrealistic pace (easy and slow) could be detrimental but I do believe if this is balanced with correct loading of an appropriate intensity (event specific), economy can managed. I am thinking of athletes in other sports also, both cyclic and skill based, that may practice at event specific intensity and low intensity to gain the benefits of both training methodologies.

Once again I totally agree with your description of flexibility and have not seen many others describe this in such a concise way. As I am sure you have seen we often see this in climbers who gain great passive flexibility yet still cannot put this into practice due to the muscle function at its new length. If only ballet warm ups were used more in climbing walls :). Having watched the Japanese senior and junior teams recently I can certainly see they have a fantastic combination of active flexibility along with maintaining great muscle power. As you have said, this functional flexibility is very balanced with technique which becomes very specific at such a high level. It will be investing to see whether competition climbers can continue to perform at the top level in outdoor climbing as the type of movements and techniques become more and more specialised beyond standard movements.

I could not comment on Alex’s mental game but I am looking forward to seeing him apply his abilities to climbs which truly challenge him. Having spoke to him in training, his buy in to ‘the process’ is awesome and is a great role model for up and coming athletes.

Looking forward to seeing you guys at the youth symposium in November.

Cheers

Ollie Torr

Lattice Training

Hi guys,

great and interesting analysis about the recent two best sportclimbers on the planet!

If I may, I will put my thoughts into it…

You were absolutely right with the finger-strength scores which we test frequently with Alex, too. Problem here is, that finger strength at a certain point (long time high performance training) will not significant improve anymore as it underlies muscle fiber specific mechanisms, which are genetically determined respective only trainiable at certain “windows” of age.

Aerobic efficiency in climbing on the other hand is a component of fitness, which underlies many different factors (as you mentioned: recovery during rest or climbing, soft grip, etc.), even when tested you can do it in rather different ways. Thus it is trainable over the whole climbers career and in most of the cases you will improve well and fast, if you train it.

The big problem on this topic is: What of the different factors should be emphasized?

Checking restpoints, adapting a specific climbing rhythm for a route or trying to climbing faster are things you will learn best in a route itself. Cognitive capacity of thinking fast during climbing in onsight mode for example is mostly related to experience.

Climbing fast is much more difficult to learn and is a highly individual aspect! Adam is pretty fast, but that doesn’t mean that Alex climbs slow. We worked for years to find an individual rhythm for him where he is feeling well with precision and at the same time is saving his energy.

I am not the friend of this endless extensive interval sessions some trainers practice, my opinion is, that you have to constrain the climber to climb effective and economic and this is hardly possible with many of the aerobic training protocols published so far…

Flexibility is another fact but its meaning for climbing performance is not deeply understand yet. I think there are three factors: basic flexibility (in which Alex has excellent scores), functional flexibility (which is the preliminary stage of good technique) and specific flexibility (which is more route specific). When I see Adams movements in some Flatanger routes I would put this ability in the third class.

Measuring and comparing technical abilities is the most challenging thing in climbing for me at the moment. It is much more difficult as many expect! The individual part is very high. I have climbed with Adam and climbed for nearly 13 years with Alex now and can say that both of them are technical extraordinary skilled climbers. But, and here we are: both of the have strength and weaknesses in their style and here is the crux of it to work continuously over a long time. For me it is the second important thing in Alex (and many peoples!) climbing training.

The most important thing in Alex training at the moment is the mental part. He just needs the vision to see, where his abilities can lead him: far beyond his recent efforts! And we improve step for step: Stay tuned 😉

Patrick Matros

Sport scientist, Headcoach of Kraftfactory and Alex trainer for 13 years

Hi Patrick,

I was wondering if you could expand a little on the topic of “windows” with regard to finger strength. Are you saying that there are certain points in a person’s physical development where maximum finger strength is determined? Is this window related to the person’s age, or is it related to how long that person has been climbing and/or training? Also, what are you referring to with “muscle fiber specific mechanisms?”

Thanks so much!

Jacob Luciani

Hi! How deep is your test (flat?) edge and how long did Alex hang on that and with how much weight. Cheers!

20mm +/- 0.1mm. The max hang test is a 5 second one-arm hang. Alex managed a full five seconds with +18kg and weighed 57kg at the time of testing.

Acknowledging that I’m a few years late to the party:

Alex weighs 57kg and Adam weighs 68kg

Alex tested at 132% of body weight = 57kg x 1.32 = 75kg

Adam “tested” at 112% of body weight = 68kg x 1.12 = 76kg

I understand that the issue re: climbing performance is strength:body weight, but how do you guys conclude from your data that Alex has stronger fingers when Adam is able to support more weight?

Hey Christopher, it’s just as you say: we’ve found the more important metric to be %BW held rather than absolute weight held, and Alex is stronger in that metric.