International Women’s Day: Research Stories

At Lattice we have a team of coaches who have dedicated themselves to understanding female physiology and how we can best work with it.

This is a relatively new area so we use a blend of theory, research, CPD, and learning from our community on the Lattice Women’s Community Facebook group (check it out if you haven’t already, link here).

1. Firstly, let’s recap what happens during our cycle

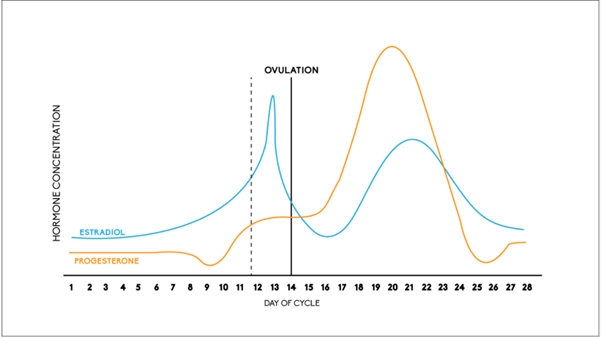

Estrogen and progesterone fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle. These hormones have an effect in our reproductive organs, but also in the rest of our body.

This is what a textbook cycle might look like… but of course, we are not textbooks! The point at which we ovulate and the degree of change in our hormones may vary from person to person, but also between cycles.

2. Estrogen impacts muscle mass and strength –

It also plays a role in our soft tissue stiffness and joint laxity. Estrogen is linked to serotonin and endorphin production. Progesterone plays a role in water balance, thermoregulation, and respiration.

Changes in these hormones can impact our performance due to changes in mood, stroke volume, body fluid volume, sympathetic activity, injury rate, ligament laxity, RPE, strength… the list goes on!

How we experience our cycle is very individual and there is a lot of variation! Tracking is a great way to get to know your own cycle. (There are lots of apps available to try, check out Maddy and Ella’s recommendations below).

3. What is the research?

There are studies that have found significant differences in balance, strength, endurance, injury occurrence in different menstrual cycle phases… but there are also studies that show no change. So what is going on?

In “The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” the group found;

- The quality of evidence was “low”.

This means that the methodology of many of the studies was considered poor. This largely comes down to menstrual cycle phase verification and the fact that individuals can have different cycle lengths and ovulate at different points within their cycle.

- There is a lot of variation between results (not surprising when we consider the variation between individuals and the sample sizes).

- The largest effect size was seen between the early and late follicular. For many this may ring true for many as the early follicular phase is when we start our period, and it is common to experience symptoms that may impact performance. The late follicular is the lead up to ovulation when estrogen is on the rise, which can be linked to feelings of high energy and motivation.

4. There are a few things we need to be aware of with this review…

- This review looked at acute performance, not adaptation to training over time using periodisation methods that take menstrual cycle into account. In a separate review, it has been found that DOMs and loss of strength post-exercise are influenced by the menstrual cycle phase.

- These studies test performance in relatively basic tasks, the tests are focused on the lower body and are rarely bodyweight dependent. They may not reflect how we perform in sport. Climbing is a complex mixture of physical and mental challenges, and as we all know can’t be narrowed down to maximal pull strength!

- This review didn’t separate different forms of exercise, such as strength vs endurance exercise and they grouped athletic and non-athletic studies together.

Given that the impact on strength and endurance may be different, and that different populations may be effected differently, this may contribute in part to the minimal findings.

- Research looks for significant differences, and this may not always be in line with what is a meaningful difference to an individual. Especially in the world of sports performance where a small change in performance can make all the difference.

- For example, no statistically significant difference was found in 100 m freestyle swimming times between early follicular and late luteal phase.

BUT on average, athletes swam 2.3 seconds faster in the late luteal phase compared to the early follicular phase.

1.95 s separated the 1st and 8th placed female swimmers in the 100 m freestyle final during the 1992 Olympics. Therefore, 2.3 seconds could be significant to a swimmer!

5. What about our perceptions of our performance, do they matter?

In “The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review”;

The group only looked at the athlete population and included athletes’ perceptions of performance. It also separated strength and endurance-based tests.

- When it comes to athletes’ perception of performance there is more agreement between studies and athletes feel their performance is relatively reduced in early follicular (menstruation) and late luteal (PMS) phases.

- Perceived performance is an important consideration as someone’s beliefs can result in an actual change in performance via a placebo (or nocedo!) effect.

When it comes to the objective measures;

Studies looking at variation in strength across the menstrual cycle show more differences between cycle phases than those looking at endurance – though this difference still varies between studies!

- More performance outcomes were relatively reduced in the late luteal phase than any other phase.

- This is frequency of change rather than magnitude of change – this is different to the finding of the systematic review which looked at magnitude. This indicates that PMS or the declining sex hormones prior to day 1 of bleeding may reduce performance.

6. But what about adaptations to training over time? The previous reviews looked at acute performance on a given day, but we are often looking to progress over time.

In “Effects of Follicular Versus Luteal Phase-based Strength Training in Young Women” the group found;

- A greater gain in muscle mass and strength development when strength training was focused in the follicular phase compared to when it was focused in the luteal phase.

- This has led to the “gain then maintain” approach to strength training

7. So what does this mean for us as individuals and climbers? When it comes to variation throughout the menstrual cycle, we need to take an individual approach. We can do this through tracking over a 3-6 month period to see when we experience symptoms that could be linked to our cycle. It is important to look at this over numerous cycles as there are lots of factors that may affect our climbing such as stress at work, or a busy family week.

8. Based on information from tracking and a good understanding of our training goals and priorities we can sync our cycle with our training periodisation.

- Strategically schedule deload weeks when negative symptoms are experienced.

- Prioritise training sessions when we can get the most out of them.

- Look outside of our training and climbing for strategies that may help (a personal one here is Mg to help with sleep and PMS!).

Thanks for reading, I really hope that you have found something useful within this, to take away for your own training. Or perhaps that you have just learnt something new – as education and knowledge on these subjects are so important for all of us!

Make sure you follow us on our social channels for more posts and updates on these topics. We run a #womensseries every Wednesday, so keep your eyes pealed.