Climbing my first 5.14a with Lattice Training – Part 1

This is a story of a journey to climb my (Adam Fiala) first 8b+ (5.14a). Climbing 5.14 can be perceived as an elite climbing performance, but the fact is that this grade is being climbed way more often nowadays. This, however, is not the point. I chose to write a story for a different reason. I couldn’t get to this grade “just” by climbing and I had to learn a lot of new things and step out of my comfort zone. This might as well be the story of how I climbed my first 5.12 or 5.13 but it so happened that the process to climb 5.14 was the most challenging but also the most memorable one.

The path to finding my project

After discovering climbing at the age of 13 it took me around 3 years to climb my first 7c and 2 more years to climb my first 8a (at the age of 18). I was never a very physically strong climber but my fingers were decent and my height certainly helped me a great deal. On the other hand, my core strength and overall body tension were severely underdeveloped which caused me to struggle on overhanging terrain. I learned how to use my strengths and that allowed me to have some early climbing successes.

By the end of 2015 I had climbed several routes in 8a+ range and was ready to try the next level. I set my sights on an 8b enduro route called Lahko noč Irena at Misja Pec in Slovenia, but ultimately felt like I had bitten off more than I could chew. I tried every trick I could think of, refined all the beta, rested properly, and it still seemed like I wasn’t physically able to do it. Throughout 2018 and 2019 I focused more on sport climbing and sent a few more 8b’s and at the end of the season in 2019 I decided to try a route called “Tanec s vlkmi” (“Dance with the wolves”).

Illustration by WildSheep

Tanec s vlkmi is one of the best climbs I’ve tried, but its beauty doesn’t lie in aesthetics, height or exposure. It is the movement that makes it special: The main crux of the route (a cross move about halfway up) really suited my strengths, and the rest positions that other climbers use didn’t work for my height. And so, this became my long term project. I decided to craft a training plan focused on building the power endurance that was much needed for the route (and that I was lacking greatly) but it was clear that I already had the prerequisite strength required for the route.

Why being my own coach didn’t work

When I look back at that time now, I realize how much training I was doing. I kept a training journal back then which serves as a great testimony to how much I was overtraining. Back then I thought that training hard meant doing two sessions a day — one in the morning and one at night. Now that I understand what my body can actually handle, I have to laugh. Why on earth did I try to do a boulder session AND an endurance session on the same day? I now know that 3-4 intense climbing sessions a week are enough for me. I knew very little about training although I thought I knew a lot.

One day I found myself browsing the Lattice Training website. I was always tempted to hire a coach but there were a few things holding me back.

- I was a bit embarrassed to hire a coach. I was worried about standing out from my climbing friends. Everyone was training by themselves so why shouldn’t I? Was I not smart enough to self-coach?

- I think somewhere on social media or in his book Dave MacLeod said that he thought that remote coaching doesn’t really work. Because I remember stuff like this and I love Dave’s work and climbing, this idea was always in the back of my head. I do think that this statement is true in some cases but definitely not every time.

- It’s expensive! I don’t like to spend money recklessly, so convincing myself that paying for coaching was worthwhile was a real crux. When I started climbing, climbers would hitchhike to the crag, sleep in a cave and were usually “getting groceries” in a dumpster by the supermarket.

I think what eventually convinced me to contact Lattice was a strong feeling that I needed to make a change. So I eventually contacted them and subscribed to the Performance Coaching Plan despite all my doubts and my training journey began!

Hiring a coach

I got really excited right after I committed to hiring a coach. I suddenly felt less pressure on myself because I essentially handed Lattice the keys and let them take care of my training!

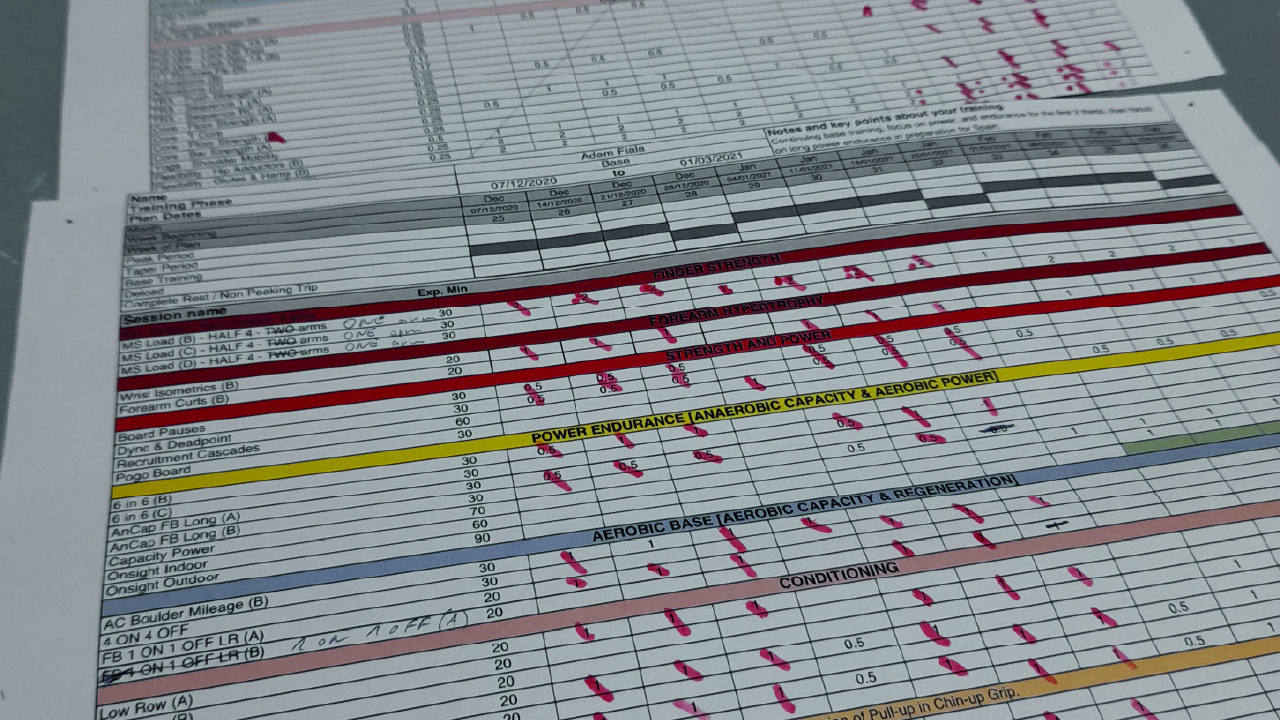

The Intake process with Lattice was pretty smooth and I got assigned to Coach Raf. The first step was to complete an assessment. I got instructions to perform a series of tests over two days with a rest day in between. Basically they test pretty much everything related to physical climbing performance. The cool thing about these tests is that you can compare your results to a database of other climbers and see how you stack up against others who climb at your goal grade. The results also factor in things like gender and height. If you want to find out more, Lattice owners Tom and Ollie do a great job of explaining their testing method in the Training Beta podcast here.

Before I got my results, I thought I knew what to expect. I assumed my finger strength was decent but nowhere near anything special. For my general conditioning results such as push ups and pull ups I knew that my results might be good when compared to the general public, but for someone specializing in climbing and wanting to break into the 5.14 realm, it is “a bit” low. The assessment report was detailed and summarized my strengths and weaknesses and the Lattice team did a great job of politely telling me that my results were significantly worse than what they would expect from a climber of my current grade. In short, my body strength was deficient and my endurance was terrible.

I did not score higher than what was expected for my grade in any of the tests.

I thought that was very accurate and confirmed what I already thought. The results of my physical test were really poor but that said something about my climbing. For most of my life I wasn’t really training effectively even when I thought I was. Most of my hard sends were done thanks to my technique, tactics, beta and (sometimes) my height. In a way I was proud to “only” be able to do 10 pull ups and climb 8b at the same time. Soon after receiving my assessment results, I received a training plan in my inbox and all I had to do was to start training!

Lesson No.1 – Training Load

It took a while to figure out all the workouts and the key thing at the beginning of the training block was communication with my coach. I must give credit to Raf for answering my many questions. When I read our e-mail communication it seems that there wasn’t a question I did not ask: Can I reduce intensity by 5% for my fingerboard session? Is it ok if I swap this aerobic session for a slightly different one? Can I stretch between hangs (seriously?)? It seemed that Raf’s patience was endless. In hindsight I regret that I didn’t take advantage of that to ask about the future of the world economy or what the weather will be like on the weekend. I am sure he would answer that as well! Maybe I’ll do that next time…

How did the actual training feel? The ability to handle the workload comes back to the training history of an individual and for me… let’s say I was VERY unaccustomed to regular training. Every workout was destroying me, especially basic things like core, pull ups, rings and push ups. I even found stretching sessions tiring. And an anaerobic climbing session? I felt wrecked after that.

In the first 3 months I learnt an important lesson: how much workload I can handle consistently. That means the quantity of all the workouts that I can complete in a week, considering I will do that for a few weeks in a row (I trained for 3 weeks and the 4th week was a deload week). So, how did we figure out the final form of my training week? The process was really simple and really humbling: My coach just took away one workout after another until I was able to cross out all the exercises in each week while being able to continue with another week of training. One big disadvantage of this approach: My ego took a big hit and I couldn’t tell people I do double days anymore. Advantage: I found out how to be a better climber.

Lesson No.2 – gaining weight isn’t a bad thing!

The climbing community I grew up in always put a big emphasis on being light. The typical climber I knew was skinny. You almost never saw him/her eating anything other than nuts, the occasional musli bar and a bowl of pasta in the evening. I adopted this attitude and I always kept sense of my weight. My friends would say that I eat very little which I thought was completely normal and, in fact, healthy.

What finally helped me find the root of the problem was coincidence. After a full day of training I was cooking and contemplating what was ahead of me. I knew the next day of training was supposed to be pretty hard. I was eating my dinner thinking that, once again, I will probably bail on my training tomorrow because, once again, I will feel tired, irritated and generally “down”. As these thoughts passed through my mind I not only ate my dinner but also my lunch for the next day – a bowl full of sweet potato fries.

Next day I woke up and my muscles were sore and I was tired but I was able to push through and complete the workout (I even enjoyed it by the end!). I knew right then that this is it – this is what it’s supposed to be like. It should be hard but it shouldn’t be impossible. I later consulted a nutritionist and they pointed out that my body fat is very low and my basal metabolism is quite high (around 2100 kcal) which confirmed my own conclusion – that I need to fuel more. So that’s what I started doing.

However, the real crux was yet to come. As I started properly fueling my body and increasing the volume of training, I also started gaining weight (partly muscles and partly fat as well). Weight is such a common topic amongst climbers and the reason is simple. Weight is perceived as a one dimensional metric and it seems to correlate with performance in a linear relationship. You get lighter, you climb better. The other option is to improve the other side of the equation which means improving your shape – your strength, endurance and other aspects of performance. In theory, you can improve in small increments for a very long time (until you reach your genetic potential). However, you can only achieve so much with weight loss. At some point you just can’t get any lighter. Of course I knew all that, I’ve read the theory many times the same way you read this post. But I felt about it the same way I feel about communism: It makes sense and it sounds right but everyone knows it doesn’t work.

I confessed to Raf about my doubts. He was convinced that I’ll be able to compensate for the additional weight with increased physical ability. I also asked about this issue on the Lattice 365 – the discussion forum (that is available to their members). Here’s what their coach Maddy told me:

I think climbers often underestimate the impact that calorie restriction can have on mental health (motivation, concentration, general well being), as well as injury risk. Pete Whittaker did a good Flog (I think this is a blog on Facebook!) about a trip he did to Norway after trying to diet down… basically he was miserable but luckily maintained his friendship with the understanding Tom Randall! Based on this I would say not to compare yourself to the “fall 2019 you”, especially as your body composition shows you have very low body fat. Given this, if you did diet you would likely lose muscle mass, which as you have said is in a desirable distribution. Muscle mass is obviously good for strength and power, but it is also good for our health and metabolism. Personally, I have gained around 4-5kg since I started training and reduced my body fat (I was around 56 kg when I climbed 8a-b and around 60 kg when I climbed 8c) and I feel much stronger in my body for it. However, weight gained (even if in a desirable way through muscle development in the upper body) can impact finger strength and skin. So then the question is: has your finger strength also improved? And does your project have really sharp holds that may cause issues? The latter is quite a niche situation, but may be one where dropping a little weight (note only up to 2 kg is recommended to prevent disruption to hormones such as testosterone) could be beneficial for a peak. When it comes to the “notorious dieters” in climbing history… like with most things I think these stories are often rose tinted. What we never hear about is the burn out, injury, impact on well being, how well they age, impact to fertility and bone health (particularly for female climbers, but also for males)! Nor do we ever know how well they would have climbed if they had fueled themselves better, or how much kinder they might have been to their belayers

This little insight into someone else’s experience was crucial. It helped me realise that it’s not just a theory and that it can actually work. My doubts about the training program were eased and I stopped being so anxious about the fact that I’m gaining weight. For some perspective, I was 78kg when I first tried my project. I was 83kg when I sent my project!

Giving it a go

Right at the end of my three month block, I was able to go to Slovakia to try the route. I was still in the training phase so I didn’t expect much. When I got there though it is fair to say that I got my ass kicked. Technically I did some good links, climbing the first and second half separately in one hang. In reality it felt desperate. To be fair I wasn’t supposed to be at my peak yet so the average performance was to be expected on the route.

Thanks to the lockdown that came in the Fall, this was the last time I climbed on my project in 2020. After a small break, I resumed my training in November and that started my longest, most sustained period of training ever. This was going to be a truly memorable winter for me because – for the first time in my life – I experienced the magic of hard training.

Stay tuned for part 2 of Adam’s journey to Dance with the Wolves…

To read Adam Fiala’s extended 5 part blog post of his journey to Dancing with the Wolves, head to his personal blog.

It’s impressive how well you maintained your core strength all while keeping the weight. Lol. I havent ever gotten that courage to climb on that level. Maybe I’m just too soft in the hands still. I suppose I’ll have to inspect the order in which I put my climbs together…… Tend to rush to the dot on the map to make a super star out of my climbing career. Thanks for the report. Time to drink my coffee and cozy up under the covers.