Flexibility, Climbing and Performance; What, Why and How? Part 1.

Flexibility is the ability to move through a range of motion and is an essential motor ability for any movement. In the context of flexibility development, we usually refer to increasing the range of motion around a joint that is limited by the muscle. This does not include the range of motion allowed by the joint capsule or bone structures, which may be referred to as the mobility of the joint.

Flexibility should be referred to in four different modes; passive-static, passive-dynamic, active-static and active-dynamic. Where passive means using no effort to contract the muscles and active means using effort to contract the muscles.

To put these into context here are examples of where each mode of flexibility might apply;

- Passive-static: Perhaps the most common method of stretching where one would lay in a relaxed stretch and hold this position still for a given time.

- Passive-dynamic: Rarely used and not practical for most purposes. This would look like a partner moving a limb into a stretch in a dynamic movement.

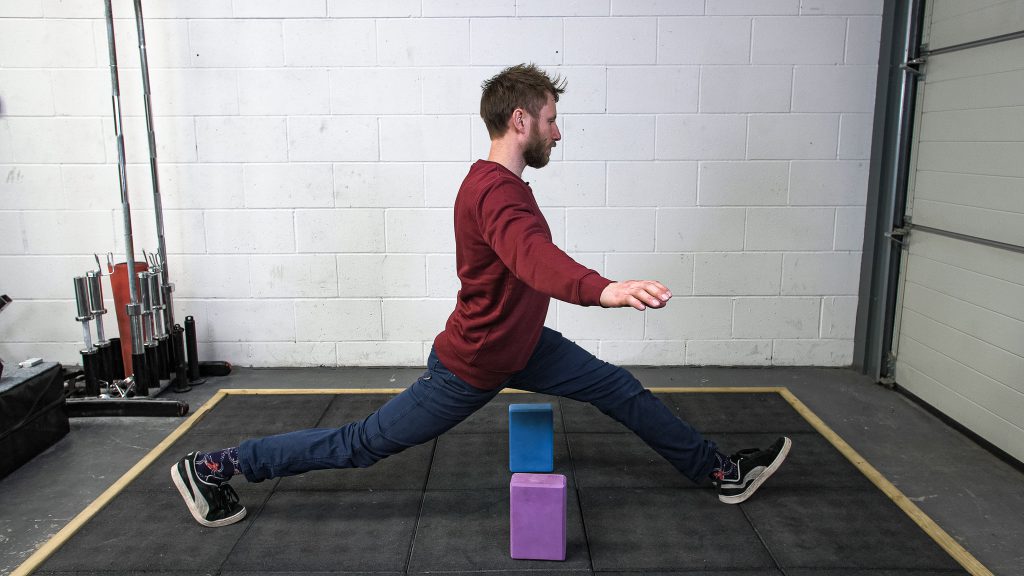

- Active-static: Holding a stretch but with intent put into contracting either the stretched muscle (agonist) or the antagonist to this muscle. E.g. Holding a long lunge/front split position or lifting the front leg in a hip flexor raise, respectively.

- Active-dynamic: Moving in and out of a stretch using your own force. This can be performed at different speeds e.g. high velocity leg swings/kicks or slow tempo horse squats. Important note: the velocity of flexibility is sport/movement specific. Muscle spindles (involved in the stretch-shortening cycle) have both velocity and tension specific components.

By using these four categories of flexibility we can identify any movement and/or exercise. It also removes the need to use the term “mobility” which is often confused or given to describe active-dynamic modes of flexibility.

To keep flexibility sports specific, we must identify the modes of flexibility used in the sport along with the range of motion needed by the sport. If we take Taekwondo, for example, an athlete must assume close to a full side split position and do so at near maximal velocity to land an effective side kick to the head. Therefore, training must practice active-dynamic modes of flexibility, ideally in movement patterns used in competition.

However, one does not just start kicking above their head and training must be progressive like any other form of training. In fact, one of the major limiting factors of dynamic flexibility is, static flexibility. Due to the elastic and contractile nature of the muscle-tendon unit, dynamic flexibility will always be limited by our passive flexibility. Therefore, we must “raise the ceiling” of our dynamic flexibility potential, by increasing our passive flexibility, even if it does not first appear to be highly sports specific.

For sports specific transfer of flexibility, to sports performance, we must develop strength through the whole range of motion. In fact, building strength in the end ranges of movement is an effective method of increasing flexibility. This will be discussed more in part 3: How?

We know physiologically a muscle can produce less force at either a lengthened or shorten state (google Strength-Length curve). However, this does not mean we cannot build strength at longer and longer muscle lengths. The fact an indivuidal can train to go from an average level of flexibility to full side splits, even if this takes time, demonstrates we have plenty of muscle length to access and strength to develop. Your current “end-range” is unlikely to be genetic limit unless you have been training flexibility for years or experience mechanical block of the joint structures. Therefore, we can develop strength along side length. As we increase range of motion, the previous muscle length that was once near end range is now well within our comfortable range, meaning we can easily develop a high level of strength here. The elevated “Van-Damme” splits is a great example of strength through range.

~ Jean Claude Van Damme in the film ‘Bloodsports’.

The role of flexibility in climbing?

Rock climbing is so unique in many ways. No two climbs are the same and every individual will interpret and move differently on just one climb, or even a single movement. In this way, climbing offers endless movement opportunities and it only makes sense to assume some of these will require a great deal of flexibility.

~ Photo by Craig Bailey

I would go as far to say that flexibility is as important as strength and fitness. And these three physical components are equally important for someone that wishes to be a “well-rounded” climber and athlete. We will discuss why and where flexibility is most important on Part 2: Why?

Check out Part 1 of our recent video below, for more tips on climbing vs flexibility…

I hope you enjoyed reading! Be sure to check out part 2 & 3 for more on flexibility for climbers.